THE LAST JOURNEY: MI6 INVOLVEMENT IN THE MURDER OF BENIGNO ‘NINOY’ AQUINO AT MANILA AIRPORT

As China Airlines (CAL) Flight 811 began its decent to the international airport at Manila, capital of the Philippines, a round faced, bespectacled passenger disappeared into the toilet. When he came out, he was wearing a lightweight bullet-proof vest beneath the jacket of his white safari suit. “Of course, if they hit me in the head, I’m a goner anyway,” he joked to his companions. Just before the aircraft landed, he bowed his head briefly in prayer, and then sat back, calm and composed.

PHOTO TAKEN BY CIA/MI6 ‘JOHN DOES’ ON BOARD FLIGHT 811

It was approximately 1pm on 21st August 1983, and Benigno ‘Ninoy’ Aquino was coming home from three years of self-imposed political exile in the United States to lead the growing opposition to the government of President Ferdinand Marcos. Aquino was anything but a welcome guest to Marcos, who had once kept him in prison for more than five years. The Philippines government had refused to issue him with a passport to re-enter his own country; more seriously, it had warned that his safety could not be guaranteed if he did come back. Aquino was travelling under an assumed name yet, at the stopover in Taipei before the final leg of his trip, he had received alarming news when he had telephoned his wife Corazon in the United States. His face white with shock, Aquino told one of his aides: “They’re going to get me at the airport, then kill the guy who did it.”

The CIA and MI6 in a joint operation were monitoring all calls to his wife.

Aquino’s arrival in Manila was expected with rapture by his many supporters. The capital was full of yellow ribbons, symbol of his party, and some 20,000 excited Filipinos had gathered at the airport to welcome him, among then the politician’s 75-year-old mother. The government had prepared its own greeting, a massive security operation at the airport designed to seal off the entire passenger arrival and the tarmac in the vicinity of Aquino’s aircraft. Even so on the short flight from Taipei, Aquino’s aides made no secret of their concern for his safety. He was subdued, but still defiant: “I can’t allow myself to be petrified by the fear of assassination and spend my life in a corner,” he was reported to have said.

The aides were proved right in all their concerns and fears. Less than 60 seconds after leaving the aircraft Benigno Aquino lay on the tarmac, blood gushing from a massive wound at the back of his skull. A few feet away from him lay the body of another man, dressed in blue trousers and a white shirt. There was pandemonium around the aircraft as heavily armed Filipino troops and security men screamed into their walkie-talkies, mingling with airline officials and the shocked passengers from Flight 811. Outside the terminal, rumours that something dreadful had happened spread quickly through the vast crowd who were waving banners that proclaimed: “Ninoy, you are not alone.”

A number of foreign journalists and television crews had been travelling with Aquino and, although security men tried to prevent them from sending out dramatic stories, their accounts were soon making headline news around the world. All were broadly agreed on the sequence of events after the aircraft had parked at gate 8. First onto the air-bridge ‘tube’ after it was connected were three or four uniformed soldiers who approached Aquino and began to lead him along the tube towards the main door. As they left, other guards in plain clothes prevented journalists from following, and finally closed the main door at the end of the tube.

The last time any of the journalists saw Aquino alive, he was being escorted by at least five uniformed men onto the platform of the steps that led down the tube service door to the tarmac below. A few seconds later, a single shot rang out then, after a brief pause, two or three more. Inside the aircraft people rushed to the windows to find out what was going on, and saw Aquino face down in his own blood. There was no sign of the uniformed troops who had been with him in the tube just a few seconds earlier but, as the journalists watched in horror, several members of the airport security unit, Aviation Security Command (Avsecom), fired at the prone body of the second man.

One in particular, placed his automatic rifle on the man’s body and coldly pumped bullet after bullet into his stomach. Other Avsecom men menaced the people watching from the CAL aircraft by firing shots in the air. As they ducked below the windows, the journalists just had time to see Aquino’s white suited body being bundled into an Avsecom van and driven off at high speed.

When the passengers from Flight 811 finally disembarked, they passed their shocking account on to the frantic well-wishers outside the passenger terminal. Salvador Laurel, the leader of the opposition party, Unido, grabbed a loudhailer and announced: “Our beloved Ninoy has returned, but you may not be able to see him. Eyewitnesses say that he has been shot.”

The stunned crowd began to disperse, and Aquino’s family arrived home in time to hear the announcement on the radio that doctors at Fort Bonifacio-Aquino’s old prison camp-had pronounced him dead on arrival.

It was five hours before the Government allowed the story that had horrified the world to be reported within the country, and a whole rumour fuelled day before President Marcos publicly presented the official version of events at Manila Airport. Looking frail and ill, Marcos asserted that he had “almost begged” Aquino not to return. His killer, Marcos said, had clearly been a professional, firing a single shot from a .357 Magnum into Aquino’s head from a range of 18 inches. Aquino’s security men were not armed, the President insisted, but they had tried to shield him with their own bodies.

Official briefings later provided the press with more information. The alleged assassin was 5 ft. 6inches (1.67 metres) tall, weighed about 12 stones (80kg), and was between 30 to 35 years old. The only clue to his identity was the word ‘Rolly’ embroidered on the waistband of his underpants and an ‘R’ engraved inside his gold wedding ring. Yet even without a name to go on, the Marcos regime had no hesitation in attributing the killing to a communist plot, deliberately designed to blacken the Philippine government with its allies abroad, especially the United States. President Reagan was due to visit Marcos later that year. According to officials, Aquino’s killer had disguised himself in the uniform of an airport maintenance worker in order to penetrate the intensive security. When Aquino arrived on the tarmac from the service steps, he had rushed out from his hiding place beneath the CAL aircraft, shoved past the escort and fired the fatal shot. Avsecom troops had then shot him dead.

Two days after Aquino’s death, his widow Corazon and their children arrived in Manila for his funeral, President Marcos announced the formation of a special commission under the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court to undertake “a free, unlimited and exhaustive” investigation into the murder. It was swiftly rejected by the Aquino family, the opposition party and the influential Catholic Church, all of whom accused the government of choosing “Marcos mouthpiece” to carry out cover up. The President subsequently made a somewhat extraordinary offer of £30,000 reward for information leading to “the arrest of the killer or killers” and this was quickly ridiculed.

Had not Marcos already assured the nation that the assassin was the man in the blue trousers, in the pay of the communists, whom the troops had shot?

There was mounting disbelief that the security authorities still could not identify the alleged killer, despite having his fingerprints and other physical leads.

Surely, the opposition leaders insisted, a professional hit-man would already be known to the police?

One paper made the headlines “Anyone out there knows Rolly?”

Other equally uncomfortable questions were being raised about the Marcos version of events. As the opposition leader, Salvador Laurel, pointed out, how could a lone gunman have penetrated the tight security cordon of some 2000 troops without inside assistance?

How could he have known exactly where to lie in wait for Aquino, who came down the service steps instead of disembarking normally?

Who were the soldiers with Aquino just before he died, and where were they now?

Why was the alleged killer riddled with bullets instead of being captured for questioning?

Some of those questions are now answered in a document signed by the Special Division of the Philippines Supreme Court Justice CIPRIANO A. DEL ROSARIO.

Of all people accused, indicted, jailed the most curious is “Indicted/Accused person number 41” called John Does.

That of course emanates from the US justice system where an unknown person accused of a crime is simply referred to as “John Doe.” It is used for a party whose true identity is unknown or must be withheld in a legal action, case, or discussion. In this case the name is John Does used in the American sense and by using the plural more than one. The significance of such is only understood after a detailed analysis of the case.

Back in 1983 as pressure on the authorities mounted, a name for the dead man in the blue trousers was finally released, nine days after the assassination. He was Rolando Galman, officially described as a “notorious killer and gun for hire.” Government sources reported that Galman was known to have links with left-wing subversive groups. But any hope that this would reduce pressure from the opposition for a truly unfettered investigation was quickly shattered.

Soon rumours began to spread like fire in Manila regarding Galman. According to testimony and interrogations years later by an MI6 officer the family stated that Galman had been taken from his home by armed men four days before the murder of Aquino.

The family confirmed to the MI6 officer, who had been asked to review the case in 1984, that two days after the Aquino murder more armed men had picked up Galman’s common law wife Lina and held her for several days the first of a number of mysterious summonses. Lina was never to be heard of again leaving a baby boy Rolando orphaned. The boy lived a nomadic life a few years with Lopino Lazaro the family lawyer but moved from house to house regularly.

Colin Figures the then head of MI6 had ordered a confidential report on the murder and an MI6 agent was sent to Manila to look into matters. The report back to the Director General in June 1984 caused Figures some considerable consternation and in 1985 he took early retirement at the age of 60. In 2006 he died after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease according to the official report. The new MI6 Director Chris Curwen a Cambridge graduate ensured the report was made subject to a “non-disclose” order lasting 50 years expiring 2035.

For the Philippine Government in 1983 however, a further sensation followed. Philippines air force officers, it was established, had picked up Galman’s mother and sister after the killing and held them incommunicado for four days before the corpse was publicly identified. All this fuelled the anger of the vast crowds of Filipinos, peasants, bankers, students and office workers who took to the streets to protest against the regime’s handling of the Aquino affair.

Placards openly accused the government of having directly organised the elimination of the most effective and popular opposition leader. Underground newspapers were naming members of the escort party in whose company Aquino had passed his last few seconds alive. One particular sergeant was even singled out as the probable killer.

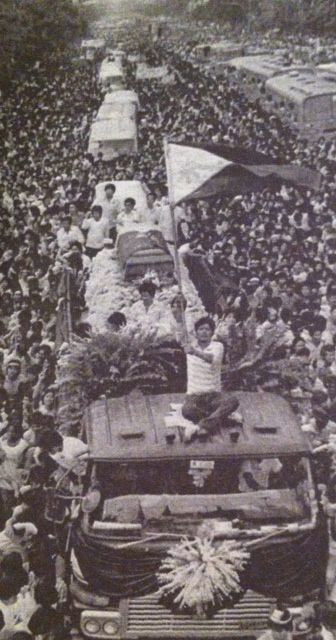

MI6 PHOTO TAKEN 31 AUGUST 1983 MANILA

Early in September 1983, the government’s commission of inquiry opened its hearings. It was boycotted by Aquino’s family and opposition. One of the first witnesses was a government pathologist, Dr Benvenido Munoz. In sworn testimony, Dr Munoz asserted that the shot that killed Aquino came from a weapon pointed upwards at the back of his head. The bullet had then been deflected downwards to exit through his jaw. “It was highly controversial evidence,” the MI6 officer who attended the commission hearings reported. Aquino’s family had already announced that examination of his corpse before it was laid in state for mourners to pay their respects had established clearly that he was killed by a bullet in the skull just below his left ear, fired from behind and slightly above him, which had travelled on a sharp downward trajectory to exit just below the mouth.

These findings were later examined and confirmed by an independent forensic expert from the United States and England.

PHOTO TAKEN BY MI6 OFFICER THE HOLE WHERE THE BULLET EXITED THE CHIN IS CLEARLY VISIBLE

The alleged assassin Galman was certainly no taller than Aquino. To fire such a shot when, as the government insisted, Aquino was already on the tarmac, Galman would have had to be holding the pistol aloft at the moment of pulling the trigger. Highly unlikely, the opposition claimed, pointing out that Dr Munoz’s experience of forensic examination in gunshot cases was severely limited. As it happened, his findings were soon forgotten.

On 10th October 1983, under pressure, all five members of the commission appointed by Marcos resigned to make way for a “more credible investigation.” That very day, the commission was due to hear testimony from the five soldiers who were escorting Aquino when he was killed.

DR BENVEDINO MUNOZ DEMONSTRATES HOW AQUINO WAS KILLED

Reports from the MI6 officer that attended the hearings and pursuant to his investigation of the matter it was clear the commission was due to hear damaging evidence against the members of the escort. This, it turned out was the result of “paraffin tests” carried out the day after the assassination on four of the five escorts, all supposedly unarmed at the time, to discover if any of them might have fired a gun. The National Bureau of Investigations had established that traces of nitrate, a component of gunpowder, were present on two of the soldiers, a strong indication though not positive proof, that they may have fired a shot during the previous 72 hours.

One of them was the sergeant already singled out as the most likely killer.

President Marcos moved quickly to form a new commission of investigation, headed by the widely respected retired judge, Mrs Corazon Agrava, and invited critics to nominate four other acceptable members of the new board. The Agrava Commission began work in November and soon showed it meant business.

Most Filipinos would agree that the Agrava hearings in what the MI6 Officer described as “hot, stuffy Magsaysay auditorium” provided the nearest thing to a thorough examination of the whole Aquino affair that was possible under the circumstances. Sessions were open to the public although certain sessions that involved national security was held in camera.

The MI6 Officer described in his report how the public would “heckle uncooperative witness’s especially unpopular soldiers or policemen.”

The Marcos government never budged from its original version of the assassination and that it was a communist inspired plot carried out by Rolando Galman. The regime’s key appearance at the Agrava hearings came from General Fabian Ver, Chief of Staff of the armed forces and a man many Filipinos considered the most powerful in the land.

In fourteen hours of testimony, General Ver politely took the commission through the military’s story from the time in early 1983 when it became clear that Aquino was thinking seriously about returning to Manila.

MI6 PHOTO GENERAL FABIAN VER AND PRESIDENT MARCOS AT A PRESS CONFERENCE 23 AUGUST 1983

Not long afterwards, Ver told the commission, military intelligence began looking into reports of a plot to kill Aquino.

He admitted according to the MI6 field officer’s report that “the information was somewhat hazy and based on a conversation overheard in a restaurant.” The MI6 officer noted how this kind of "tittle tattle that amounted to fish mongers wives tales could possibly be the basis of factual information.” Ver went on to say that the assassination was carried out in such a way that blame could be placed at the hands of President Marcos whereas that was clearly not the case.

Ver initiated “Project Four Flowers” designed to collect, collate and evaluate all information concerning the possible threat to Aquino and to take “the appropriate action.” One threat was examined, according to Ver, was a planned operation by the New People’s Army of communist guerrillas, but it had not been possible to acquire solid information about this from field agents or from “MI6/CIA field officers in the Philippines.”

Ver told the commission that another theory examined by his “Project Four Flowers” was whether any of Aquino’s numerous political enemies perhaps even those opposing Marcos might want him dead. Such a possibility could not be ruled out and President Marcos himself considered that certain Filipinos had “valid reasons” to kill Aquino. But early in August 1983, with Aquino’s return inevitable, military intelligence had lost contact with “Agent Baby” an undercover man who was providing valuable information about the assassination threat. “Agent Baby” was a CIA operative who surfaced again only after the killing at the airport.

The commission did not pursue the “Agent Baby” affair not even calling him in one of the closed sessions.

William Casey and President Reagan were certainly not going to allow a CIA man to give evidence.

REAGAN AND CASEY

Ver told the commission that military intelligence had made a last desperate effort to establish whether an organised assassination plot existed, and that President Marcos had been kept informed of “Project Four Flowers” from the beginning. Ver testified that after considering all the intelligence data, he had recommended to Marcos that Aquino should be prevented from coming home for at least another month. Then he had received information from the opposition leader Salvador Laurel that Aquino intended to return on 21 August, probably on a Japan Airlines flight. Ver said from that moment the priority was to protect Aquino against any attack.

The head of the air force, General Luther Custodio, was fully briefed on the danger of an attempted assassination and a new file, “Operation Plan Homecomer (Balikbayan),” was opened, giving General Custodio total authority over airport security, Avsecom.

Two options were under consideration, according to Ver: either send Aquino away on the aircraft he arrived in if he lacked proper travel papers; or allow him to land, then take him to his old cell in Fort Bonifacio prison under the original warrant for his arrest, since the order of 1977 affirming his death sentence had never been rescinded.

The government’s last hope that warnings about the dangers to his life might persuade Aquino to stay away vanished when information from Philippines embassies abroad made it clear that he was on his way. Japan Airlines had been warned it would lose all its future landing rights if it flew Aquino in, but Ver insisted that when the decision to arrest Aquino on arrival was taken, nobody knew exactly what flight he might come on. Indeed, Ver testified that he went back to his quarters in Manila at 11am on 21 August still not knowing that Aquino was on China Airline Flight 811. At about 1.30pm he learned that Aquino had flown in and that “somebody had been shot.” Half an hour later General Custodio telephoned him with the news that Aquino was dead. Ver said he broke the news personally to a shocked and disbelieving President Marcos.

The Agrava Commission pressed Ver hard about the failure of “Op. Plan Homecomer.” Ver cited the killing of Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat and the assassination attempt on President Reagan in 1981 as examples of the failure of intense security measures. Mrs Agrava was not impressed: “With Sadat and Reagan, it was known where the assassins came from. In this particular happening, we’re finding it very difficult to determine where the alleged assassin came from-despite the fact that ten, twenty, thirty persons could have seen it.”

In addition, it is highly significant that the plan to take Aquino off the aircraft by the normal passenger exit was only changed ten minutes before the aircraft was due to land. At this point, normal security guards were ordered out of the critical area and Avsecom men took over. Even if Galman had penetrated the security cordon as the government claimed, how could he have known about such a last minute change of plan? The place where he allegedly hid in order to fire the fatal shot required prior knowledge of how the senator would be leaving the plane.

Ver was asked about reports that one of Aquino’s army escort, Sergeant Arnulfo de Mesa, had since become a lieutenant. It was true that de Mesa had been recommended for promotion since the assassination, explained Ver, but he had passed the qualifying exams long before the killing. “He has not,” stated Ver firmly, “been rewarded for anything.”

During General Ver’s testimony, members of the late Rolando Galman’s family were parading outside with posters declaring: “Father is dead. Is mother dead too?” Galman’s two children, 16 year old Roberta and 11 year old Reynaldo, testified to the commission. Their mother had been taken away for the final time by armed men in late January 1984 and had not been seen since. The children said that their mother had told them that she had been ‘summoned’ by General Ver. When it was put to Ver that she had been arrested on his orders, he rejected the allegation as an “outrageous lie.” As his testimony drew to an end, a question came down from the public gallery asking Ver to comment on newspaper reports that Aquino had named him as the man he most feared in the Philippines, and that these fears were even shared by President Marcos himself. Quite untrue, Ver protested: as commander of Fort Bonifacio prison, he had enjoyed correct, even cordial, relations with Aquino when he was held there. What about President Marcos, Ver was asked? “I am loyal to my commander in chief and he should not have any reason to fear me,” was the reply from Ver noted by the MI6 field agent that observed the proceedings.

MI6 PHOTO OF GALMAN’S SON REYNALDO GIVING EVIDENCE

General Ver’s assured performance did no real harm to the government case, but his subordinates who went before the commission were far less impressive. The picture that emerged from the hours of testimony from officers and other ranks involved in “Op. Plan Homecomer” was described by the MI6 agent in his report as “worried men clinging hard to stories that often started to break down under even the mildest of scrutiny.”

Sergeant Armando de la Cruz was a good example. Assigned to an Avsecom back-up security team on 21 August, de la Cruz was in the air bridge tube when Aquino was escorted from the aircraft, his elbows held on either side by uniformed soldiers. When he first testified, de la Cruz claimed that he was still inside the tube when the shooting started and therefore saw nothing. At a subsequent hearing, however, a videotape film shot by one of the foreign television crews on Aquino’s aeroplane clearly showed de la Cruz on the platform of the service steps, looking downwards after Aquino and his escorts had started to descend. Under severe pressure, de la Cruz admitted that he had originally lied to the commission, but he still stuck to his story that he had seen nothing.

MI6 PHOTO GENERAL LUTHER CUSTODIO GIVING EVIDENCE

The MI6 officer who covered the hearings noted particularly the following exchange in his report: “What was in the shoulder bag the video shows you were carrying? He was asked. “Lunch and a T-shirt” de la Cruz replied, “I carried my gun on my waist.” “Where was Aquino when you saw him last?” “On the tarmac.” “Are you willing to swear your changed testimony?” “Yes.”

Sergeant de la Cruz was the first Agrava witness to be warned that he could face perjury charges.

Sergeant Reynaldo Pelias was in the same security team as de la Cruz, standing inside the tube as Aquino was led towards the service door. He had helped push back the journalists who were trying to follow, Pelias testified, and had not been in any position to see the shooting. Mrs Agrava then showed him a photograph, taken by a journalist on the China Airlines flight, showing Aquino being escorted towards the door of the service steps. Pelias was visible in the photo, but claimed, astonishingly, that he could not identify Aquino. “You were supposed to provide Aquino’s security, you were there, you saw this man in front of you and you mean to tell us now that you can’t identify him?” asked Agrava.

The MI6 officer covering the hearing wrote in his report: “She summoned the commission official who habitually played the part of Aquino in recreations of the position of witnesses in the moment before the shooting. As the man crouched down, almost touching Sergeant Pelias, Mrs Agrava asked, ‘Just this close to you, right? The man you are supposed to be protecting, right?’ There was a long pause, and then Pelias replied, ‘Yes.’

THE AQUINO SECURITY TEAM ‘THE FIVE WISE MONKEYS’: MORENO, LAZAGA, DE MESA, LAT, CASTRO JESUS

Another man who had been very close to Aquino actually inside the CAL aircraft was Sergeant Clemente Casta, attached to the Presidential Security Commission and assigned that day to collecting the list of passengers from flight 811. Casta testified that when he reached the door of the aircraft, an Avsecom officer had told him to lend a hand inside. Cross examination established that it was highly unusual for anyone to enter arriving aircraft ahead of customs officers, and that Casta had been carrying a bag, about 12 inches in length, which he normally used for storing the passenger list. Casta told the commission that he had waited inside the aircraft until Aquino was escorted towards the exit, only then following himself. But once again the video film showed a different story. Casta had, in fact been standing in the tube when Aquino was led past him. On the film he appeared to have passed something to the last soldier in the escort.

MI6 PHOTO SERGEANT DE GUZMAN DEMONSTRATES HOW HE FIRED AT ROLANDO GALMAN

But the most extraordinary military testimony came from what the MI6 field officer called “the five wise monkeys” the team of five men that had escorted Aquino from his plane and down the service steps. “Saw nothing, heard nothing, said nothing.” That was their repeated theme of their evidence to the obvious incredulity of the Agrava commission and all who were present.

Despite being within inches of Aquino and regardless of the cat calls from the public and some from the commission they stuck to their story. They say nothing, heard nothing, said nothing.

Sergeant Claro Lat was actually holding Aquino’s right arm when the fatal shot was fired. The MI6 officer noted the comment from Lat in his report: “I heard a big bang, then Aquino went limp and I could not hold him up. I fell on top of him then got up and ran for cover.” The commission noted “surely you must have seen something.” His reply “No, everything happened so fast that I failed to witness it.”

Private Rogelio Moreno was a few feet behind Aquino, ideally placed to see if an assassin had shot him from behind. “Unfortunately I was looking somewhere else at the time,” he testified. The MI6 agent present at the hearings doodled on the report with the words “cover up.”

All he saw was Aquino falling and a man in blue trousers with a gun in his hand. Paraffin tests on Moreno two days after the assassination found several specks of nitrate on both hands. Moreno claimed, however, this was because he had been on the shooting range the day before Aquino’s arrival.

The commission also accepted without question the testimony of General Ver that the government did not know when Aquino was returning.

But MI6 that had been “in surveillance” of Aquino and President Marcos through GCHQ it’s base for intrusive electronic surveillance had copies of cables sent to Manila by the Philippines Embassy in Singapore which suggested that Aquino's return was not a complete surprise: At least while he was in Singapore his movements were being monitored with the help of the Singapore government on the orders of MI6. The cables remained potentially important as they suggested that departments of the Philippine government other than the military were involved in checking Aquino's whereabouts.

Further, intrusive surveillance by GCHQ was so sophisticated that it picked up unidentified persons shouting in a Filipino dialect. The voices seem to be saying ''I'll do it'' and ''shoot him.''

The evidence and material collated by MI6 should of course have been disclosed to the Commission but was not on the orders of the Director General. A review in 1984 came to the same conclusion.

The most intense evidence centred on the testimony, lasting eight hours, of Sergeant Arnulfo de Mesa described by the MI6 officer covering the hearings as “a baby faced mountain of a man.” A skilled marksman and karate expert, de Mesa had been one step behind and above Aquino on the service stairs, with both hands on Aquino’s left arm. De Mesa insisted that the escort group was already on the tarmac, heading for the waiting Avsecom troop carrier, when he suddenly felt a hand holding gun nudge his right shoulder. There was a shot, he said, and then he turned and felled the gunman with a karate chop, forcing him to drop his .357 Magnum. De Mesa said he picked up the weapon and ran for cover.

Paraffin tests carried out on De Mesa two days later had proved positive on both hands, he too however, maintained that he had been on target practise the day before the assassination. His performance was less than convincing in the face of the considerable evidence that he had been perfectly placed to fire the fatal shot behind Aquino’s left ear. He was the favourite suspect.

At the end of the escort’s evidence, a much frustrated Mrs Agrava gave them a piece of her mind. “Only two possibilities can be surmised from your testimonies. One is that Galman could not have been on the tarmac when Aquino was shot because it is difficult to believe that none of you saw him shoot Aquino. The other possibility is that all of you are not telling the whole truth, you are trying to hide something from the board.”

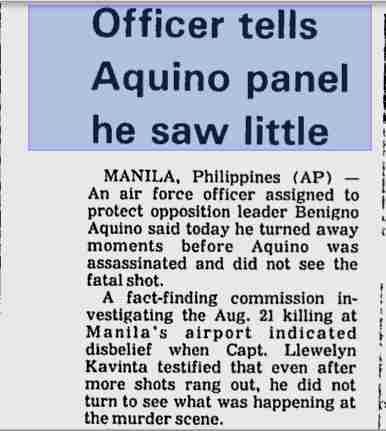

An Avsecom officer, Captain Llewellyn Kavinta, was on tarmac security duty when Aquino’s aircraft arrived at the gate numbered 8. He was shown a photo taken from inside the CAL aircraft of a man sprinting across the tarmac, gun in hand. He agreed the figure was himself. He also testified that security uses disguises, including airport uniforms, to combat hijackings. Captain Kavinta said they were ''not exactly'' similar to Mr. Galman's. He told the commission he was confused and was probably “running away from the scene gun in hand.”

Asked by Mrs Agrava why he had been running away from the scene of the killing, gun in hand after the assassination Kavinta replied “I can’t remember.”

Time Journalist Sandra Burton who was on the CAL flight with Aquino and who stayed right behind him kept her tape recorder on and captured history. On her tape, and others made by television crews, different male voices are heard saying in Tagalog, the Filipino language: “Here he comes….I’ll do it….Them, let them do it….Go on! Shoot! Shoot!”

Burton testified that as she was being forced back into the aircraft, she recorded a single voice saying, “I’ll do it!” A shot is then heard on the tape, then voices wailing, “What’s happened?” Three more shots ring out, the confusion increases and a man shouts; “He’s dead, he’ dead.” Then more shots are fired.

Burton testified that her tape recording of the Ninoy Aquino murder was an "accurate recording of what happened" and denied suggestions by military attorney that it has been tampered with.

SANDRA BURTON OF TIME MAGAZINE

Some of the testimony most damaging to the Government came from civilian witnesses. A lawyer, Jose Espinosa, exposed the government’s lies in claiming that it took a long time to identify the dead man in the blue trousers as Rolando Galman. Espinosa had once acted for Galman, and his evidence made it clear Galman was known to the security services long before the assassination, and may even have had close contacts with senior officials involved in “Op. Plan Homecomer.”

Documents, intercepts and information obtained by MI6 confirmed that Galman had been arrested early in 1982, charged with robbery, car theft and possession of an unlicensed gun. However, instead of facing an ordinary criminal court as an offender with a previous record, Galman was sent to a military detention centre, Camp Olivas, under a special order introduced by President Marcos under martial law for use mainly against political offenders.

It was in fact Espinosa that had been retained by Galman’s wife Lina to secure his release.

Espinosa told the commission that he had asked a high ranking air force intelligence officer, Colonel Arturo Custodio, for advice on securing his clients release. He even went with Custodio to Camp Olivas for a meeting with his client. In February 1983 records show Galman was released because the Philippines Defence Ministry had said there was no case pending against him.

A day or two after the assassination Espinosa had asked Colonel Custodio what he knew about the killing. Custodio replied “They’re crazy, that guy was already dead when they dumped him on the tarmac.” Espinosa had no idea “that guy” was Galman, his client. Mrs Agrava asked Espinosa what he thought the Colonel meant. Espinosa replied “I think what Colonel Custodio told me was that it may have been the military escort who shot the late senator.”

There were rumours as far afield as Washington and London that the Philippines operated a policy of killing political undesirables. It was rumoured that Custodio was linked in some way to the organisation of the ‘salvage’ teams that murdered thousands of people considered by the authorities to be subversive or communists.

It was the very reason why the CIA and MI6 were monitoring the whole country and those that were in exile.

Custodio conceded finally that he had known Galman since 1979 and that Galman had visited his home on several occasions.

GALMAN’S MOTHER WEEPS OVER HIS BODY. HIS WIFE LINA AND GIRLFRIEND ANNA

Both Galman’s common law wife Lina and his mistress-come girlfriend Anna Oliva disappeared after Galman’s death never to be heard of again.

MI6 PHOTO OF AQUINO AND GALMAN’S MOTHER ATTENDING A POLITICAL RALLY TOGETHER

Several airport workers on duty when Aquino arrived also significantly undermined the government case.

Fred Viesca, a cargo handler, testified that he was no more than 20 metres from the rear of the China Airlines aircraft at gate 8 when he heard a single shot. He looked up to see a man in a white suit fall from the mid-section of the service door steps. Viesca panicked and ran off, hearing more gunfire behind him, but he was adamant that Aquino had not yet reached the tarmac when he was killed, as the official version maintained.

A Philippines Airline (PAL) ground engineer, Raymondo Balang, bravely came out of hiding to give the commission his story. He said that he had been on the tarmac near CAL 811 when it landed and had seen the man he later discovered to be Galman among the soldiers and security men gathered there. “He was just standing there and smiling,” Balang testified.

He explained to the commission he had gone into hiding when he learned that military intelligence was looking for him. Balang’s story was supported by an account given to a US television network by Ruben Regelado, another PAL ground technician on duty when Aquino was shot. Regalado said that he fled to Japan for his own safety after the assassination. He claimed that a third PAL employee working with them had told him of seeing a man on the service stairs shoot down Aquino.

Efren Ranas offered the commission the most dramatic and for the government the most damaging eyewitness testimony. A private security guard on tarmac duty about 15 metres from the service steps to gate 8 he described how he heard a single shot when Aquino was still descending and was about four steps above the ground. After the shot, Aquino’s head seemed to be hanging to one side, and it appeared that he was being supported bodily by two of the escorts. On reaching the tarmac, they let Aquino’s body fall back to the ground. Blood was clearly visible on the back of his white jacket.

MI6 SURVEILLANCE PHOTO TAKEN ON BOARD CHINA AIRLINES FLIGHT 811

Accounts by two Japanese journalists who were aboard CAL 811 with Aquino strengthen the evidence of those airport ground workers. A special session of the commission was held in Japan to take their testimony. The MI6 agent covered that session and reported back to London.

Kyoshi Wakamiya, a freelance writer, said that he had been right behind Aquino when the soldiers led him out of the aircraft. At the door of the service steps, security men barred the way and stopped journalists from taking pictures. Wakamiya said he then lost sight of Aquino, but watched four soldiers going down the service steps towards the tarmac. They were half way down the steps when there was a shot. Then as noted verbatim by the MI6 officer: “I saw Aquino falling face down….I could see blood coming out of his head. At that time, as I was staring at Aquino, a man wearing blue clothes appeared….staggering as if he was pushed out by someone….Soon three or four men wearing caps like berets appeared, all of them aimed their guns at the man in the blue clothes, fired several shots and disappeared. The man in blue fell backwards face down.”

The MI6 agent reported to London that Wakamiya had changed his story to the commission considerably from an account he had given at a press conference a couple of days after the assassination. On that occasion, noted the MI6 agent he had claimed that he had actually seen two soldiers on the steps with Aquino pull out pistols. One had then fired into Aquino’s head, Wakamiya had insisted. But according to the other journalist on the CAL flight, Wakamiya who was a personal friend of Aquino was in a highly emotional state after the shooting.

At the end of the Second World War Japan formally surrendered not only to the Allied troops but also to the Philippine Army. Indemnifications were an important issue that had to be solved if Japan was to be restored to full membership in the post-war international community. It was imperative that Japan compensate the countries of Asia for the losses and suffering inflicted on them during the war if Japan, repentant over past wrongs, was to establish and develop new relations of friendship and cooperation with these countries. Realizing this, Japan concluded reparations agreements with the four countries of Burma, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

August 1967 the five countries of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand joined together in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to promote peace and prosperity in Southeast Asia. Although ASEAN put its initial emphasis on promoting economic, social, and cultural cooperation within the region, political coordination also had to be strengthened to deal with the unstable situation in Indochina and ensure regional security.

In 1983 the Philippines was in a serious financial crises yet 1984, 1985 and just before President Marcos fled the country Japan received favourable trading status and Marcos granted a moratorium to the Japanese Government on reparations.

Was this related to the altered testimony of the JAL employee?

The Agrava commission established that the shot which killed Aquino was fired 11 seconds after a US film crew, filing inside the CAL aircraft, lost sight of him when he was led into the air-bridge tube. On the video made by a Japanese crew, the first shot was heard 9.2 seconds after Aquino and his escorts began to descend the nineteen service steps towards the tarmac. Sergeant de la Cruz, the soldier faced with perjury charges after changing his testimony, finally agreed that the fatal shot came approximately 6 seconds after Aquino had begun to descend, when he was on about the fifth step down.

The official military view was that Aquino could have covered the distance between the top of the steps and the spot where his body fell on the tarmac in 11 seconds at a fast pace. The MI6 officer with the assistance of security officers (on the handwritten ‘request’ of Lord King then Chairman of BA) from Cathay Pacific in Manila made several visits to gate 8 to recreate the scene. The report from the MI6 officer stated that it “took between 13 and 15 seconds to descend the steps to the tarmac at a normal pace.”

The difference of a few seconds in those circumstances is anything but trivial since according to Time Magazine correspondent Sandra Burton the whole affair lasted no more than 17 seconds.

So why was Aquino killed and who killed him?

To understand the motivation and the total inertia of MI6 who were and remain active in Manila since the end of the Second World War the economy of the country and its relationship with the US/UK is vital.

At independence in 1946, the Philippines was an agricultural nation tied closely to its erstwhile colonizer, the United States. This was most clearly observed in trade relations between the two countries. In 1950 the value of the Philippines' ten principal exports--all but one being agricultural or mineral products in raw or minimally processed form--added up to 85 percent of the country's exports. For the first twenty-five years of independence, the structure of export trade remained relatively constant.

The direction of trade, however, did not remain constant. In 1949, 80 percent of total Philippine trade was with the United States. Thereafter, the United States portion declined as that of Japan rose. In 1970 the two countries' share was approximately 40 percent each, the United States slightly more, and Japan slightly less. The pattern of import trade was similar, if not as concentrated. The United States share of Philippine imports declined more rapidly than Japan's share rose, so that by 1970 the two countries accounted for about 60 percent of total Philippine imports. After 1970 Philippine exporters began to find new markets, and on the import side the dramatic increases in petroleum prices shifted shares in value terms, if not in volume. In 1988 the United States accounted for 27 percent of total Philippine trade, Japan for 19 percent.

At the time of independence and as a requirement for receiving war reconstruction assistance from the United States, the Philippine government agreed to a number of items that, in effect, kept the Philippines closely linked to the United States economy and protected American business interests in the Philippines. Manila promised not to change its (overvalued) exchange rate from the pre-war parity of P2 to the dollar, or to impose tariffs on imports from the United States without the consent of the president of the United States. By 1949 the situation had become untenable. Imports greatly surpassed the sum of exports and the inflow of dollar aid, and a regime of import and foreign-exchange controls was initiated, which remained in place until the early 1960s.

The controls initially reduced the inflow of goods dramatically. Between 1949 and 1950, imports fell by almost 40 percent to US$342 million and surpassed the 1949 level in only one year during the 1950s. Being constrained, imports of goods and nonfactor services as a proportion of GNP declined during the 1950s, ending the decade at 10.6 percent, about the same percentage as that of exports. By the late 1950s, however, exchange controls had begun to lose their effectiveness as most available foreign exchange was committed for required imports. A tariff law was passed in 1957, and, from 1960 to early 1962, import and exchange controls were phased out. Exports and imports increased rapidly. By 1965 the import to GNP ratio was more than 17 percent. Another acceleration of imports occurred in the early 1970s, this time raising the import to GNP ratio to around 25 percent, the level at which it remained into the 1990s. Imports in the 1970s were increasingly being financed by external debt rather than by exports.

The composition of imports evolved after independence as industrial development occurred and commercial policy was modified. In 1949, about 37 percent of imports were consumer goods. This proportion declined to around 20 percent during the exchange-and-import control period of the 1950s. By the late 1960s, consumer imports had been largely replaced by domestic production. Imports of machinery and equipment increased, however, as the country engaged in industrialization, from around 10 percent in the early 1950s to double that by the mid-1960s. As a result of the surge in petroleum prices in the 1970s, the import share of both consumer and capital goods fell somewhat, but their relative magnitudes remained the same.

No matter the trade regime, the Philippines had difficulty in generating sufficient exports to pay for its imports. In the forty years from 1950 through 1990, the trade balance was positive in only two years: 1963 and 1973. For a few years after major devaluations in 1962 and 1970, the current account was in surplus, but then it too turned negative. Excessive imports remained a problem in the late 1980s. Between 1986 and 1989, the negative trade balance increased tenfold from US$202 million to US$2.6 billion.

In 1990 weaker world prices for Philippine exports, higher production costs, and a slowdown in the economies of the Philippines' major trading partners restrained export growth to only slightly more than 4 percent. Increasing petroleum prices and heavy importation of capital goods, including power-generating equipment, helped push imports up almost 17 percent, resulting in a 50 percent jump in the trade deficit to more than US$4 billion. Reducing the drain on foreign exchange became a major government priority.

A number of factors contributed to the rather dismal trade history of the Philippines. The country's terms of trade have fallen for most of the period since 1950, so that in the late 1980s, a given quantity of exports could buy only 55 percent of the volume of imports that it could buy in the early 1950s. A second factor was the persistent overvaluation of the exchange rate. The peso was devalued a number of times falling from a pre-independence value of P2 to the dollar to P28 in May 1990. The adjustments, however, had not stimulated exports or curtailed imports sufficiently to bring the two in line with one another.

A third consideration was the country's trade and industrial policies, including tariff protection and investment incentives. Many economists have argued that these policies favourably affected import-substitution industries to the detriment of export industries. In the 1970s, the implementation of an export- incentives program and the opening of an export-processing zone at Mariveles on the Bataan Peninsula reduced the biases somewhat. The export of manufactures (e.g., electronic components, garments, handicrafts, chemicals, furniture, and footwear) increased rapidly. Additional export-processing zones were constructed in Baguio City and on Mactan Island near Cebu City. During the 1970s and early 1980s, non-traditional exports (i.e., commodities not among the ten largest traditional exports) grew at a rate twice that of total exports. Their share of total exports increased from 8.3 percent in 1970 to 61.7 percent in 1985. At the same time that non-traditional exports were booming, falling raw material prices adversely affected the value of traditional exports.

In 1988 the value of non-traditional exports was US$5.4 billion, 75 percent of the total. The most important, electrical and electronic equipment and garments, earned US$1.5 billion and US$1.3 billion, respectively. Both of these product groups, however, had high import content. Domestic value added was no more than 20 percent of the export value of electronic components and probably no more than twice that in the garment industry. Another rapidly growing export item was seafood, particularly shrimps and prawns, which earned US$307 million in 1988.

The World Bank and the IMF as well as many Philippine economists had long advocated reduction of the level of tariff protection and elimination of import controls. Those in the business community who were engaged in import-substitution manufacturing activities opposed reductions. They feared that they could not successfully compete if tariff barriers were lowered.

In the early 1980s, the Philippine government reached agreement with the World Bank to reduce tariffs by about one-third and to lift import restrictions on some 3,000 items over a five- to six-year period. The bank, in turn, provided the Philippines with a financial sector loan of US$150 million and a structural adjustment loan for US$200 million, to provide balance-of-payments relief while the tariff wall was reduced. Approximately two-thirds of the changes had been enacted when the program ground to a halt in the wake of the economic and political crisis that followed the August 1983 assassination of former Senator Benigno Aquino.

In an October 1986 accord with the IMF, the Aquino government agreed to liberalize import controls and to eliminate quantitative barriers on 1,232 products by the end of 1986. The target was accomplished for all but 303 products, of which 180 were intermediate and capital goods. Agreement was reached to extend the deadline until May 1988 on those products. The liberalizing impact was reduced in some cases, however, by tariffs being erected as quantitative controls came down.

A tariff revision scheme was put forth again in June 1990 by Secretary of Finance Jesus Estanislao. After an intra-cabinet struggle, Aquino signed Executive Order 413 on July 19, 1990, implementing the policy. The tariff structure was to be simplified by reducing the number of rates to four, ranging from 3 percent to 30 percent. However, in August 1990, business groups successfully persuaded Aquino to delay the tariff reform package for six months.

The problem with Benigno Ninoy Aquino was that the United States knew if he returned to Manila his party would win the 1984 elections without doubt. The CIA had made that clear. MI6 also briefed the British Government that Aquino was certain to win and that he would end up becoming President in the following Presidential elections.

His personal policy, made clear whilst in the USA having treatment was that he wanted the Americans out of Subic Bay and wanted to take back control of the country. Marcos on the other hand according to CIA Director Will Casey was “a safer bet.”

Margaret Thatcher agreed and discussed the matter with Ronald Reagan in their special relationship status. Reagan had told Thatcher that Aquino’s return to Manila would mean the end of Subic Bay and that Aquino was by far more interested in relations with China than with US/UK.

With that policy he signed his own death warrant. MI6 and the CIA made sure that Marcos was aware when Aquino would land at Manila and the rest was in Will Casey’s words “up to them.”

It was a death that could have been avoided.

Marcos fled the country via Clark Air Base in Angeles City where he boarded a US Air Force C-130 plane bound for Andersen Air Force Base in Guam and finally to Hawaii. Thatcher was not the only one to have a special relationship with the United States of America.

He died shortly thereafter in Hawaii.

Corazon Aquino became the President of the Philippines and within a short period of time she followed what would have been her dead husband’s policy to kick out the Americans from the Philippines.

The 15th President of the Philippines Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino the son of both the assassinated Benigno Aquino and Corazon Aquino has taken a different course and restored the special relations with the US by inviting the US back to Subic Bay.

Benigno Ninoy Aquino died in vain.

It could have been prevented by the CIA and MI6 but the orders were clear. This was an internal manner and Marcos was Washington and London’s man in Manila.

Aquino had been warned. Both Thatcher and Reagan like Pontius Pilate washed their hands of what they knew would be the consequences.

Marcos dealt with the situation in the only way he knew and as would ultimately be his own fate: elimination.